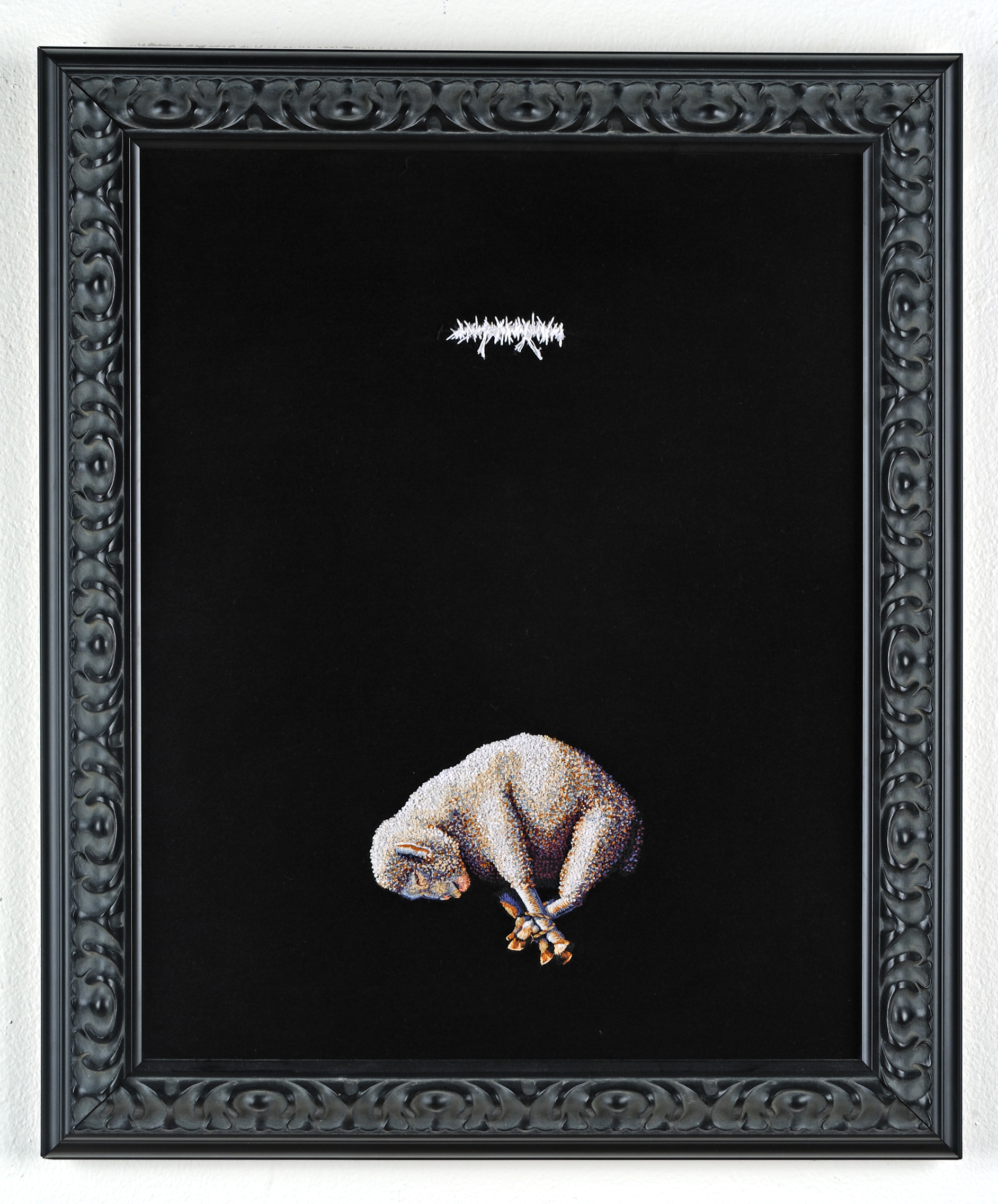

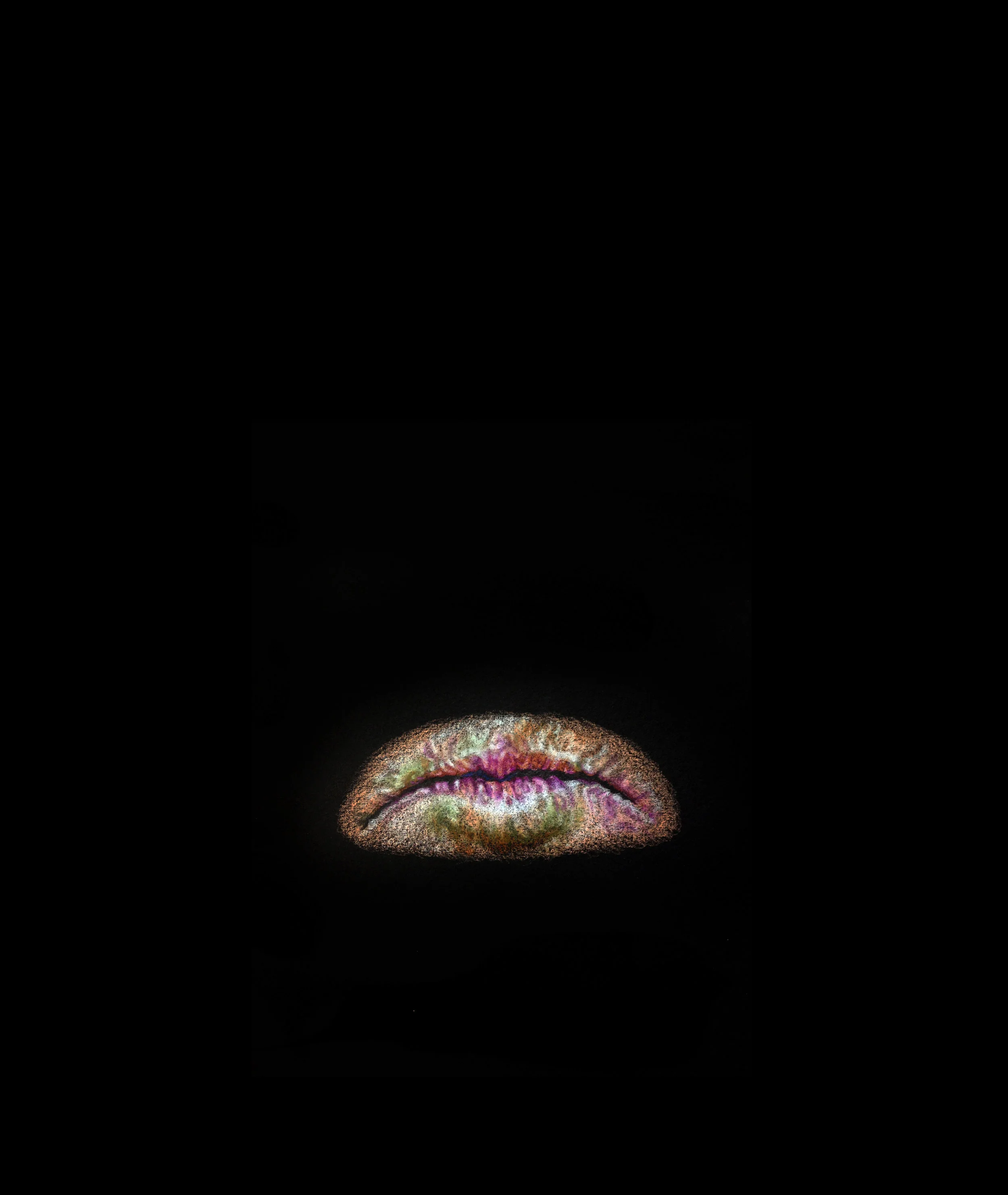

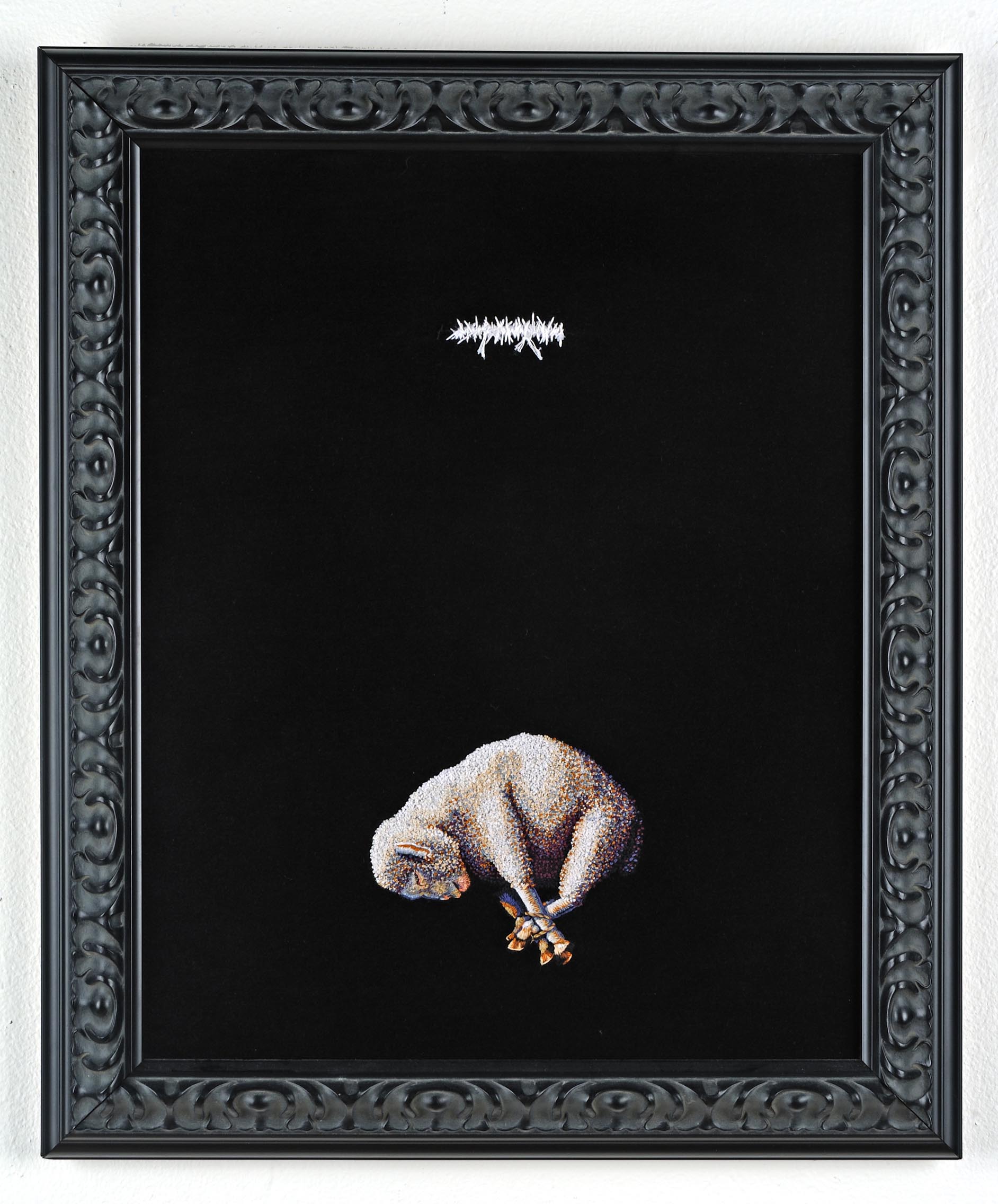

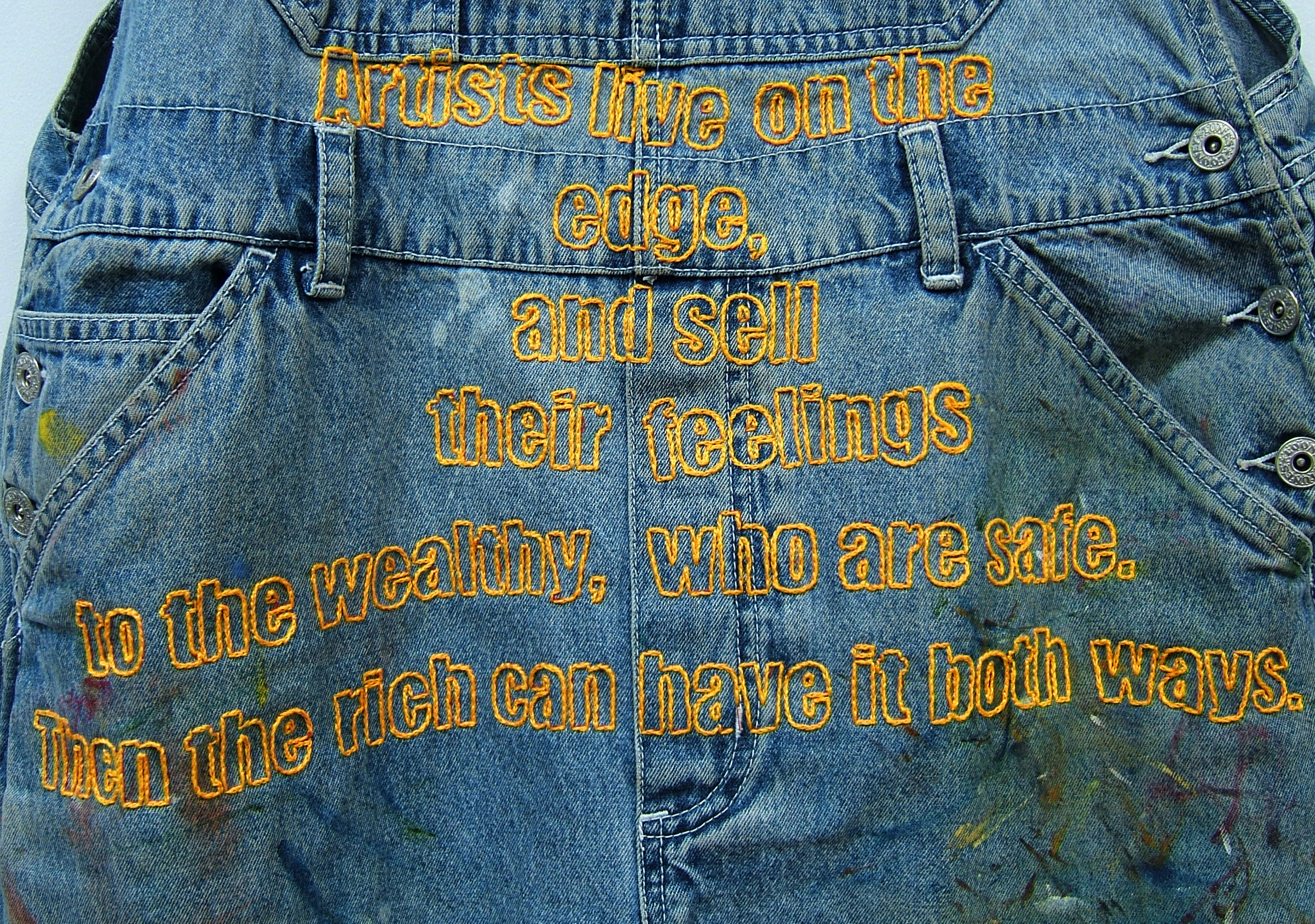

A painting series of women in various states of consciousness.

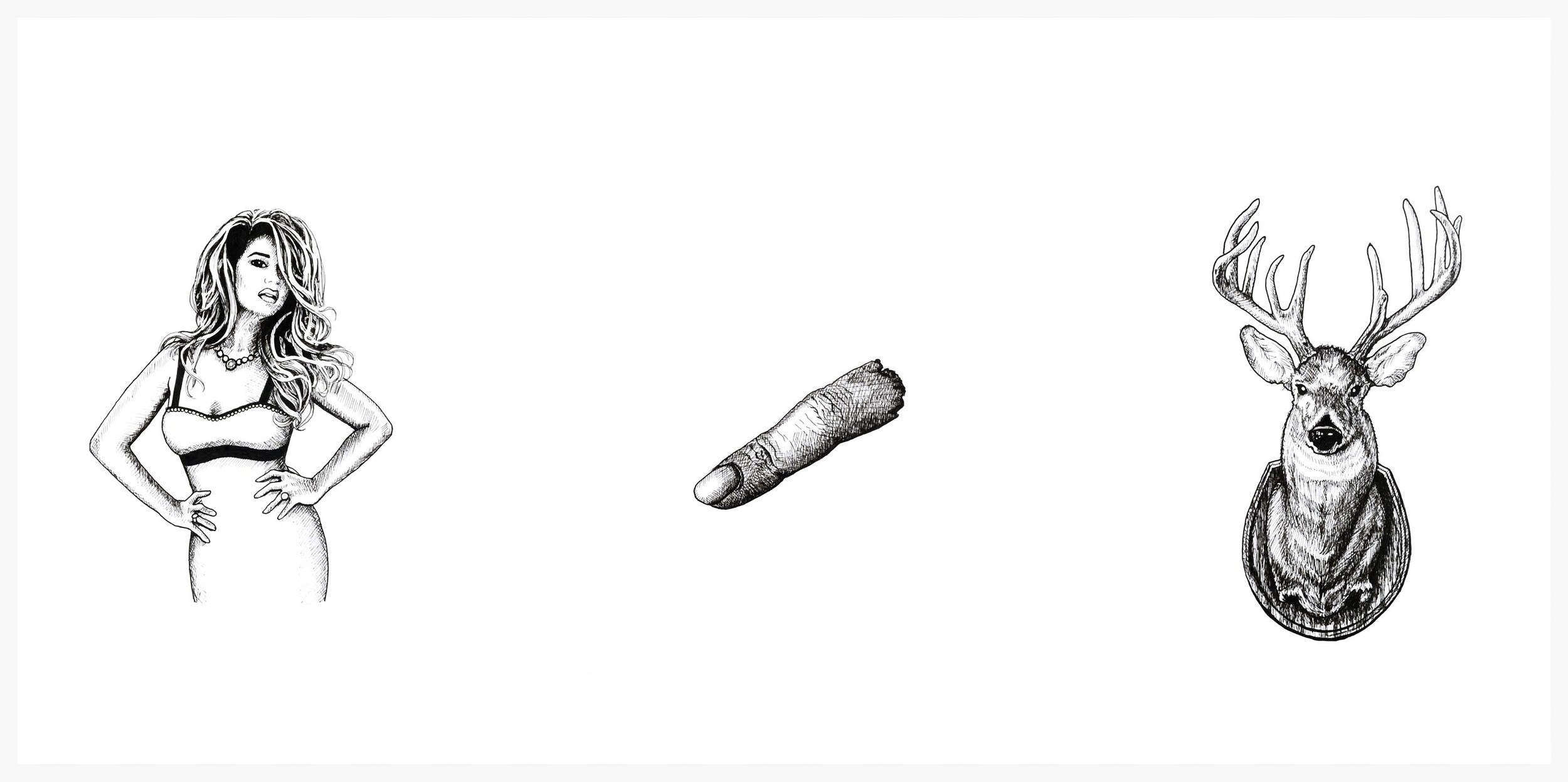

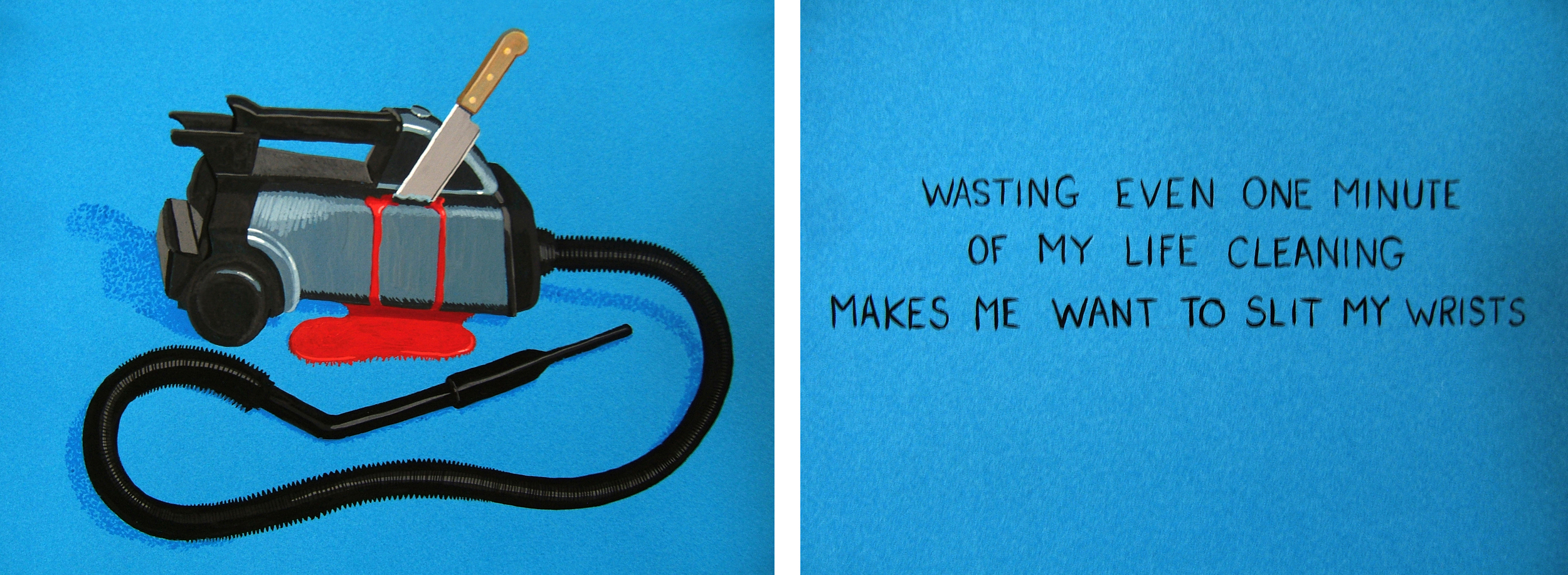

Many of the titles are real Cosmopolitan magazine articles, a publication that, at the time, seemed entirely devoted to helping women appear independent while trying to snag themselves a man.

Nora Heimann, PhD, in the catalog essay for my solo exhibition, Beauty Wrest, at The Frost Museum, writes:

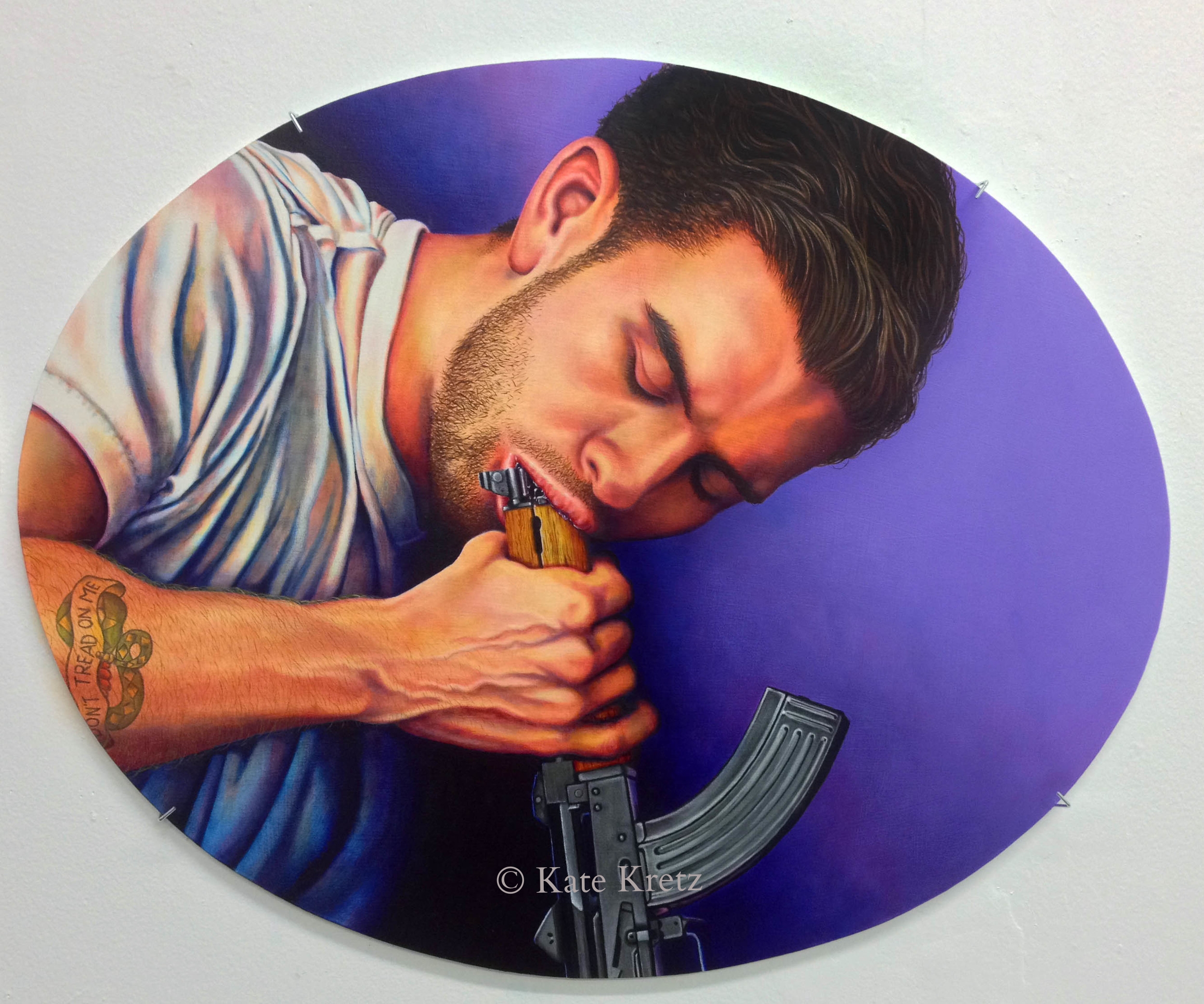

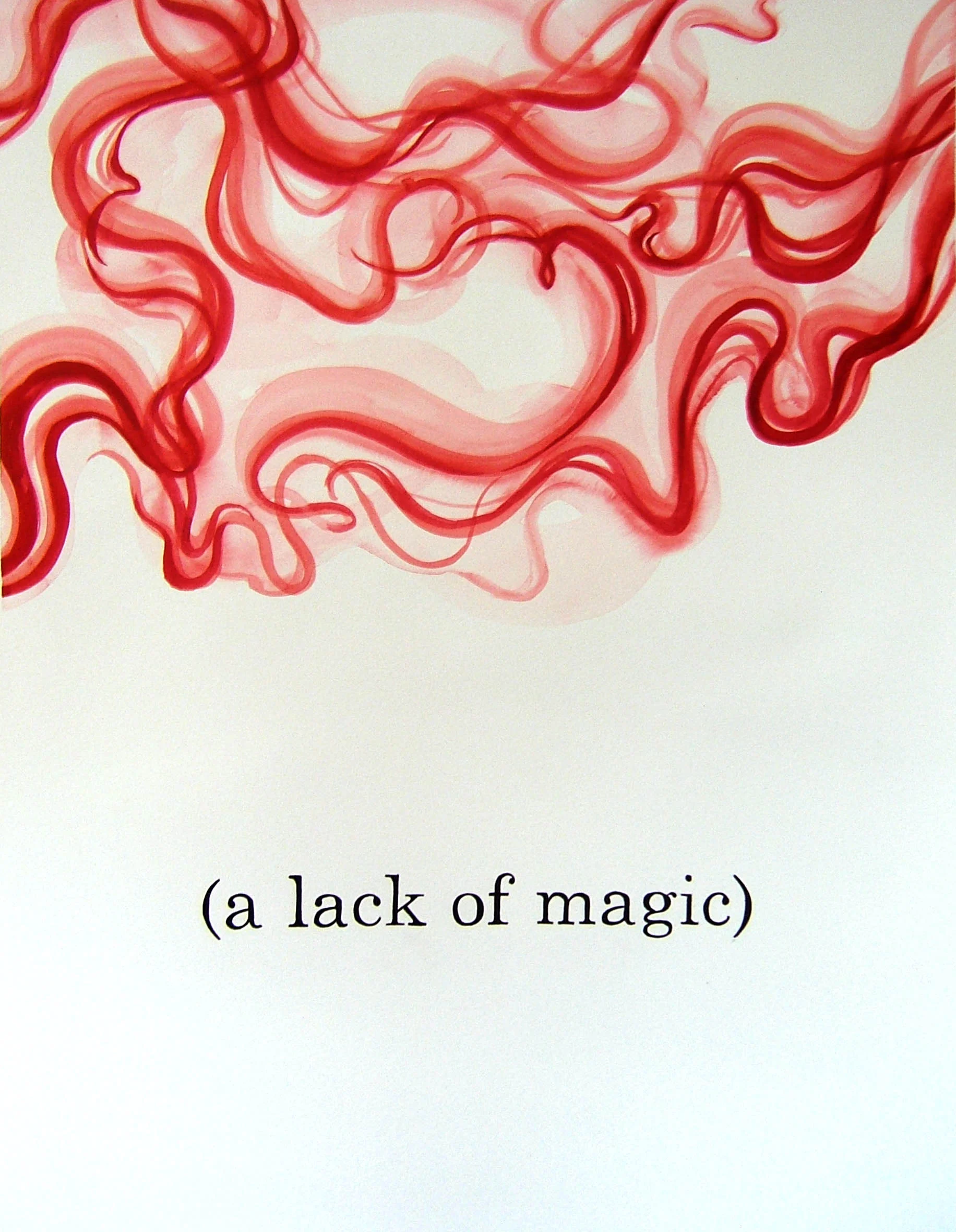

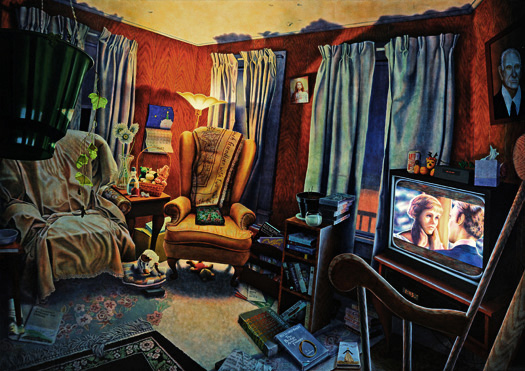

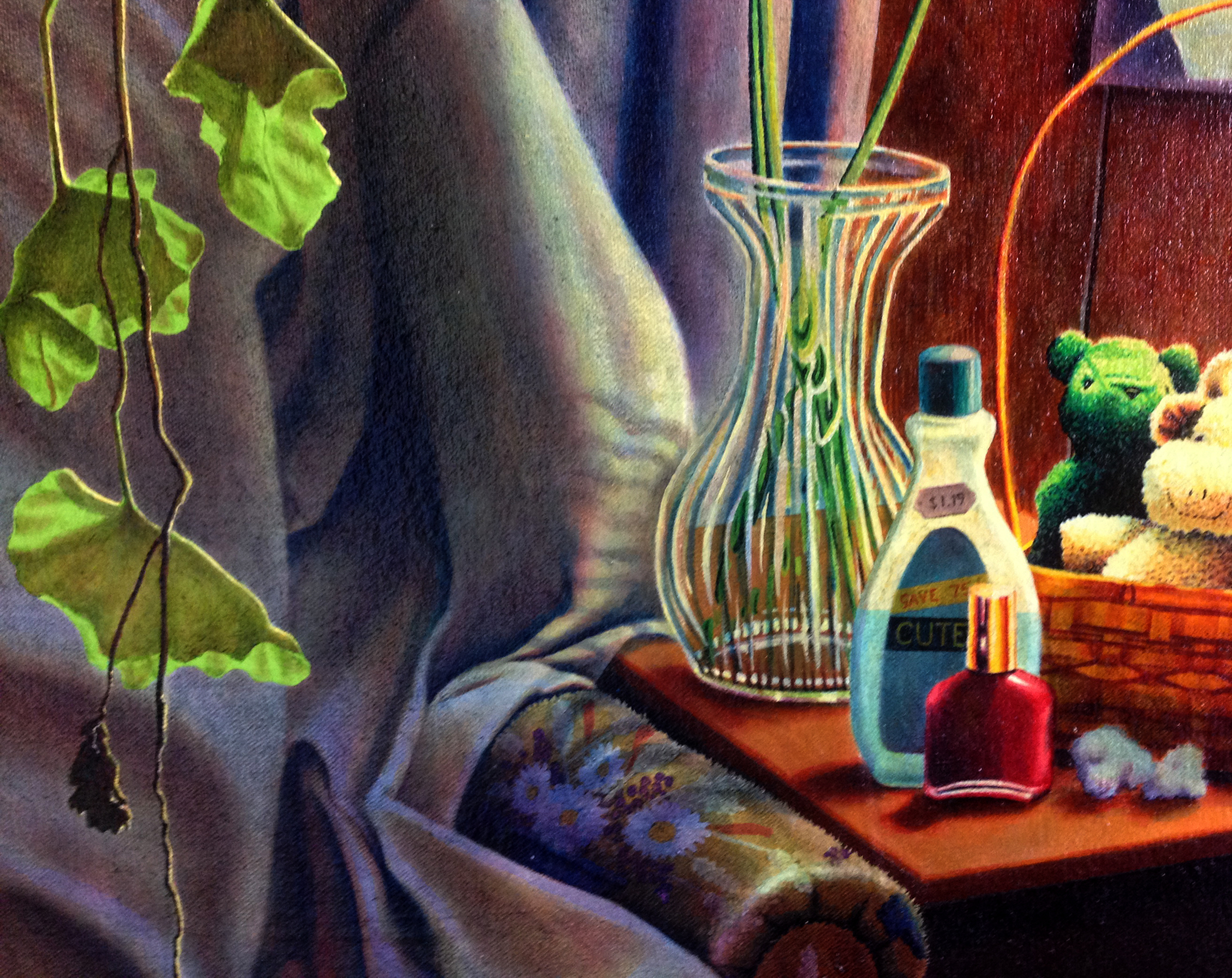

"Powerfully resonant and enticingly complex, Kretz's paintings are crafted-one might almost say wrought-with an exquisite detail that draws the viewer in, unfolding before the viewer's gaze only slowly, and only with an investment of time and effort. For Kretz, this vivid and sensual density of detail is deliberately excessive, as she herself describes it:

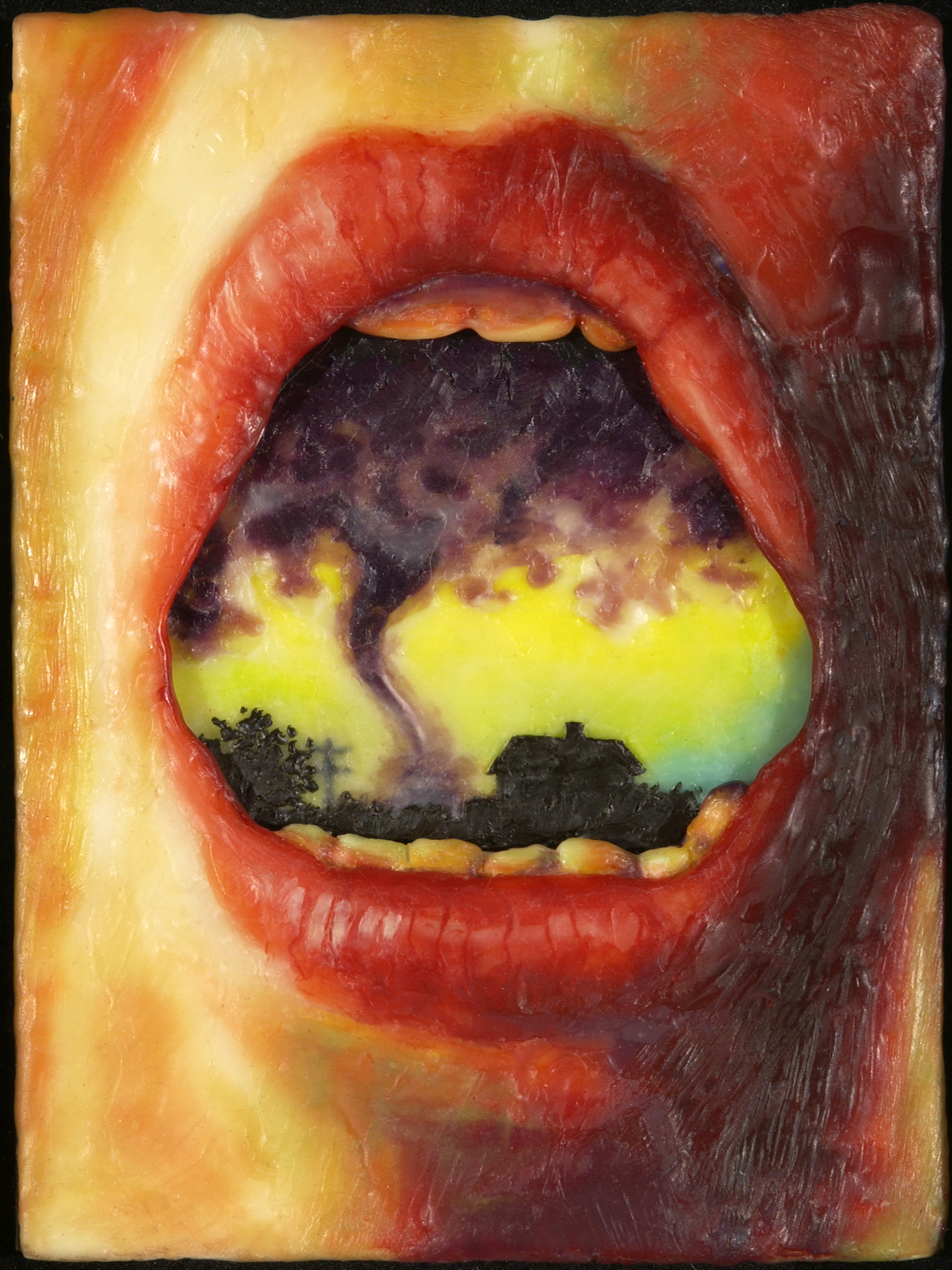

“I want to make riveting images that cannot be dismissed, executed in such a way that they demand to be examined further. I am trying to convey that moment when you come upon something for the first time, and it is so beautiful, strange or moving, that it makes you hold your breath: that moment is so out of the ordinary and magical that you want it to last as long as long as it possibly can. And if you don't breathe, it's almost like stopping time, you are suspended in that moment.”

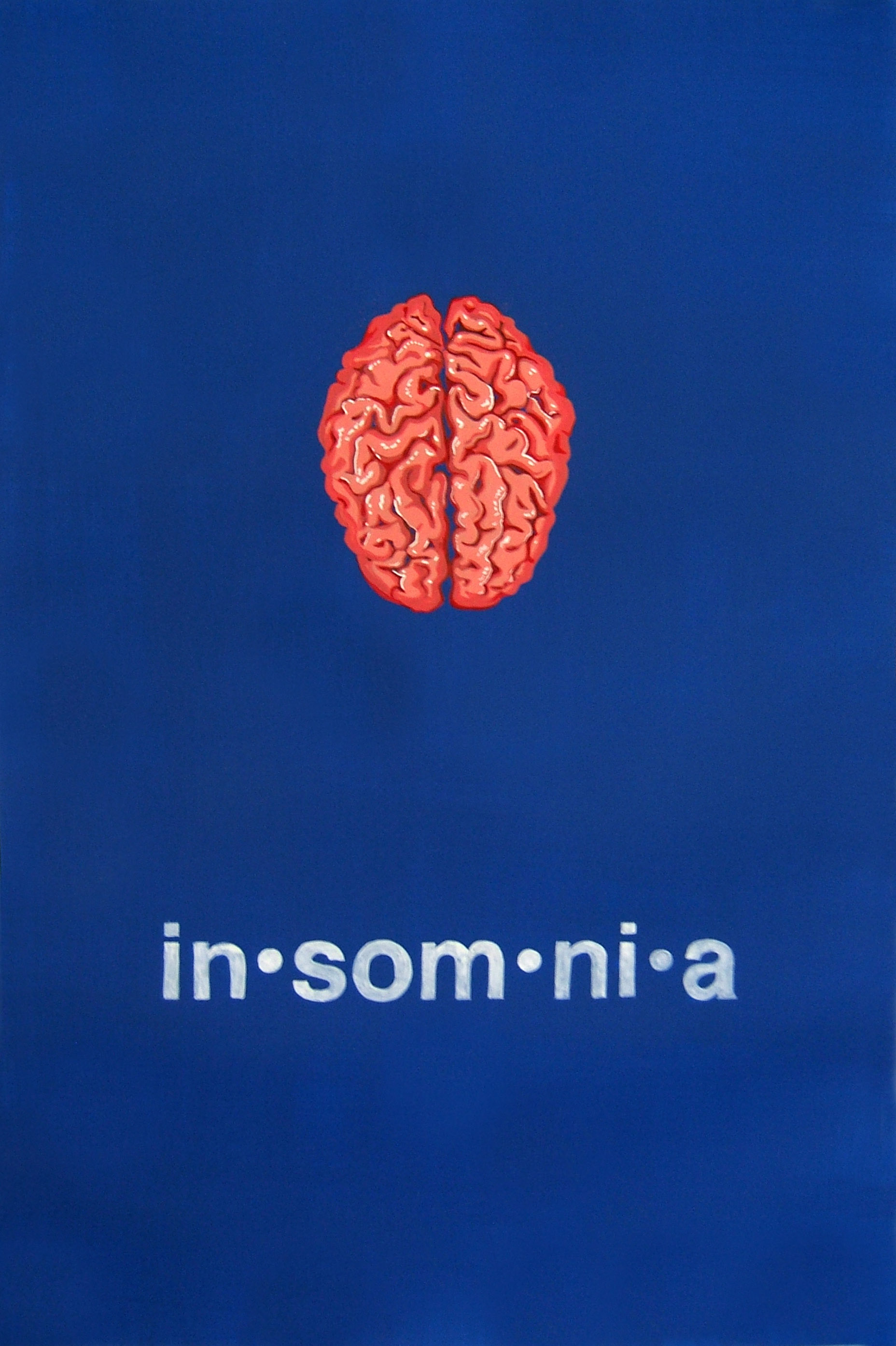

In Kretz's work, the most riveting and extraordinary images of life are set at night. Night, for Kretz, is a time of "heightened awareness," and strange, almost magical transformations....

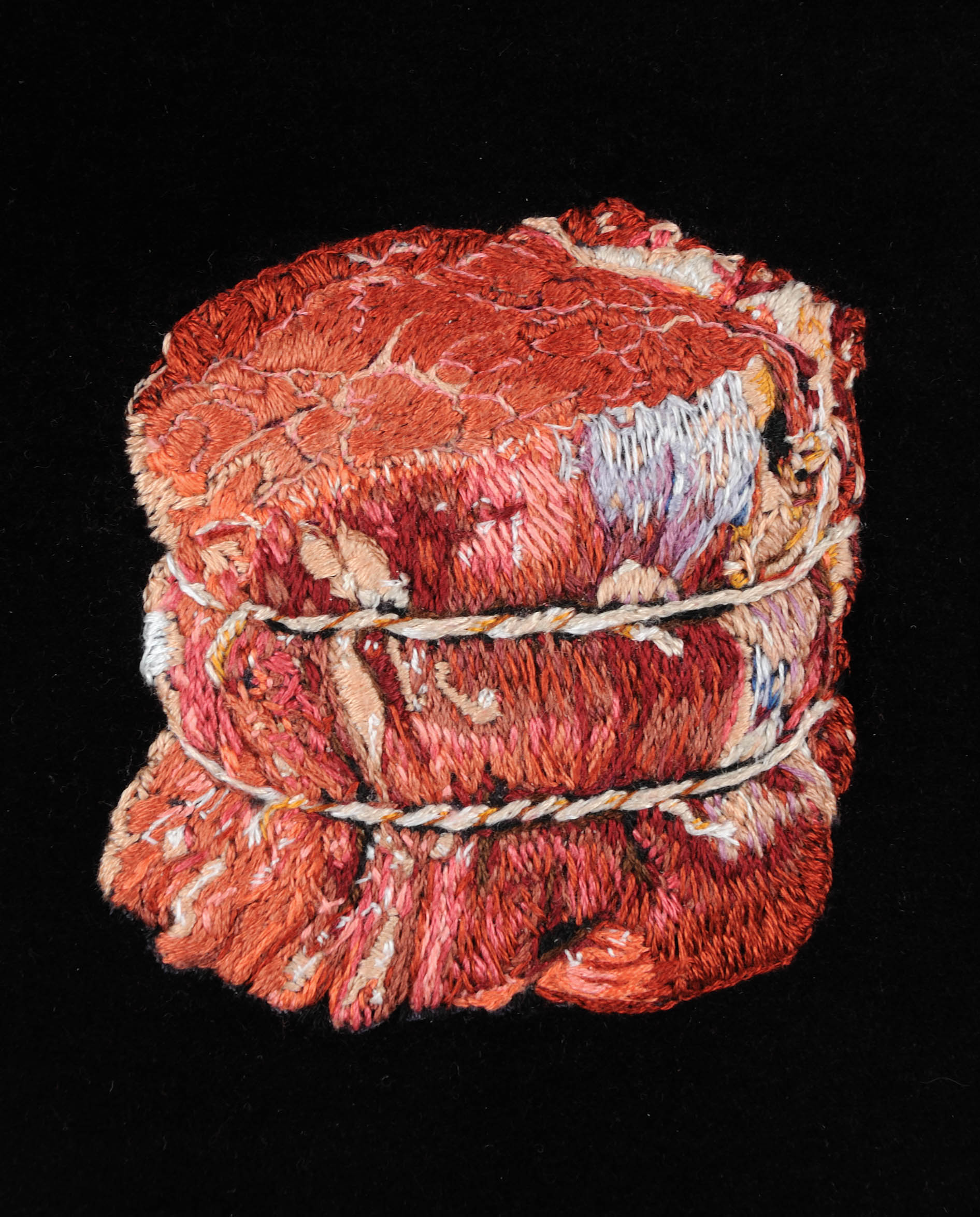

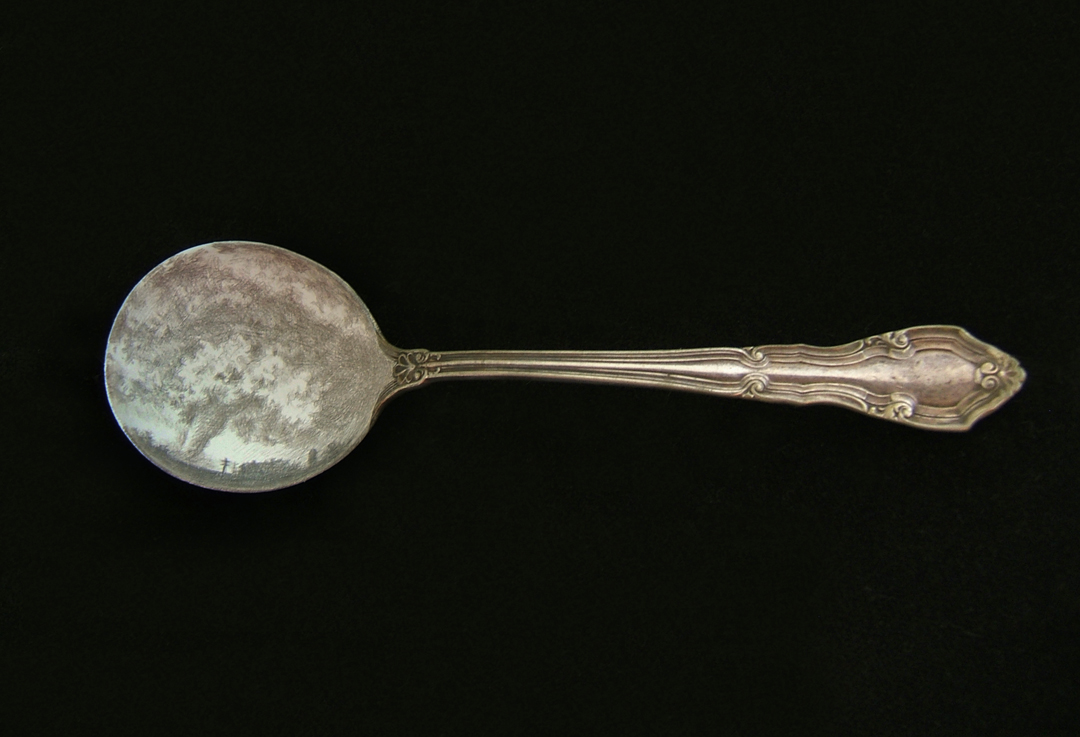

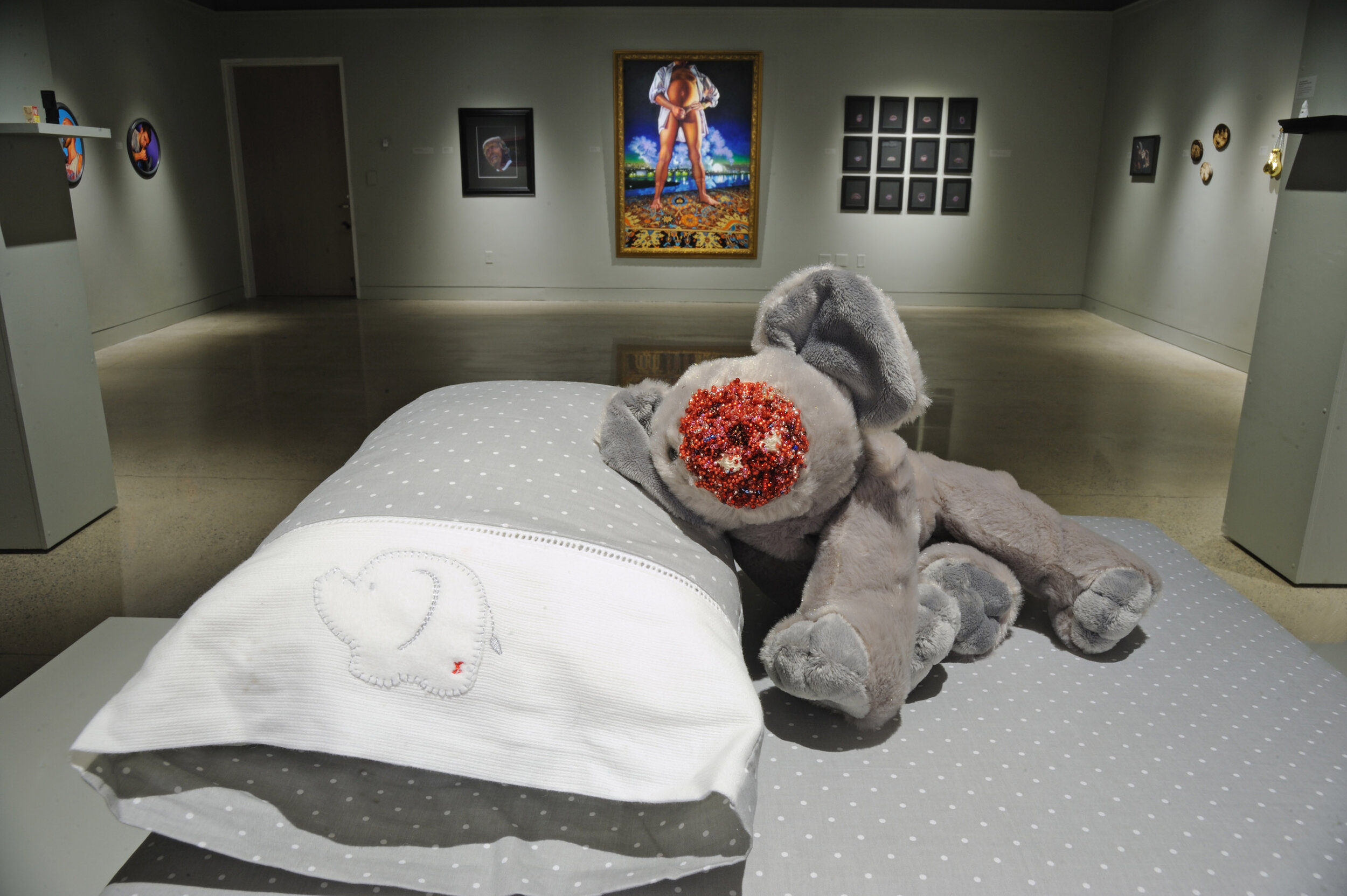

In her latest work, Kretz has continued to paint the night, now with the human figure-not the landscape-as the site for an entranced liminal state between dreaming and consciousness. In this series, women (or occasionally men) lie on their beds, or curl up on a car seat, motionless-sleeping, or buried in thought. In 3:15 and Sleeping Muse, it is a man shown tangled in restlessly knotted sheets, his golden curls (luxuriantly evocative of a pre-Raphaelite beauty) as tightly coiled about his head as the linens that bind his lean, muscular, elegant frame. These night figures are no less the musings of an insomniac than Kretz's nocturnal landscapes. In 3:15, for example, the relentless passage of time in the night, stealing minutes and hours without rest, is evoked by the disjunction between the painting's title and the luminous numerals-"3:25"-of the digital clock glowing from the shadows in the left distance, behind the still but sleepless form, whose painfully open eyes are no less bright in the dark. Most often, however, it is women that people Kretz's images of sleeping or sleepless figures.

Eyes closed or turned away, these prone or supine female bodies seem, at first glance, to be compliant and vulnerable visual tropes for the sleeping beauty story. They yield-at least superficially-their delicate, youthful forms to the viewer's objectifying gaze without defensive resistance. Upon closer examination, however, subtly disturbing, even ominous, details in Kretz's images subvert the mastering gaze and its fantasy of replete, appropriative satisfaction.... in I Let Him, But I Didn't Really Like It... (1993), a woman sleeps in the glow of candlelight, her crown of curls entangled in a richly patterned pile of lace and tapestry-clad pillows. When considered closely, however, the paint on her fingernails is revealed to be chewed, and one of her pillows is seen to be rent by a large and crudely mended tear. Here, the artist's use of a disturbing and deliberately provocative title further augments the subversion of the image's seductive appeal.

In Kretz's paintings of women asleep in cars, such as Ten Ways to Win Him Without Losing Yourself, p. 93 (1995) and He Gave Me All of His Love, But Later It Ran Down My Leg (1995), the paintings' titles remain provocative and ironic, now braving outright offense in their direct defiance of conventions of phallocentric romanticism and submissive femininity. What these titles simultaneously emphasize and seek to subvert is the submissiveness of women. This strategy seems both contradictory and especially urgent in the face of the series' aura of female vulnerability. The young protagonists curled in the passenger-side or in the back seats of cars appear open to the control of an implied male companion, seemingly vulnerable to the male gaze, if not also the male touch (back seats of cars at night implicitly evoking, in American popular culture, the possibility of an illicit encounter). Like sleep, travel is, by its nature, a temporal state; and in Kretz's work-He Gave Me All His Love..., for example-male affection and female control, alike, are similarly posited as fugitive conditions.

In Kretz's recent painting Kim Hiding (1994), what is fugitive is the woman herself, a flame-haired figure tightly crouched beneath a low bed frame. Wedged under the wooden slats and metal rails of the bed, her cheek and arm can be seen pressed to the warm polished wood of the floor, framed by a rose-colored dust ruffle behind her and the satiny, cream-and-rose colored curtain of a tumbled comforter overhead. Kim hides, as playful children do, in a place of temporary solitude; there is, however, nothing playful about her self-concealment. Kim's face-while partially masked by a tumble of hair-is clearly expressive of anger. The brilliant, glaring amber of her narrowed eyes flashes unmistakable defiance of any unwanted intrusion. As ever, the details of this painting are rich with ironic and subversive meaning: the "comforter" provides no comfort, the white high heels-well-worn yet still evocative of elegant summer soirees, or perhaps even bridal festivities-recall the torturous demands of women in society in the name of beauty and elegance.

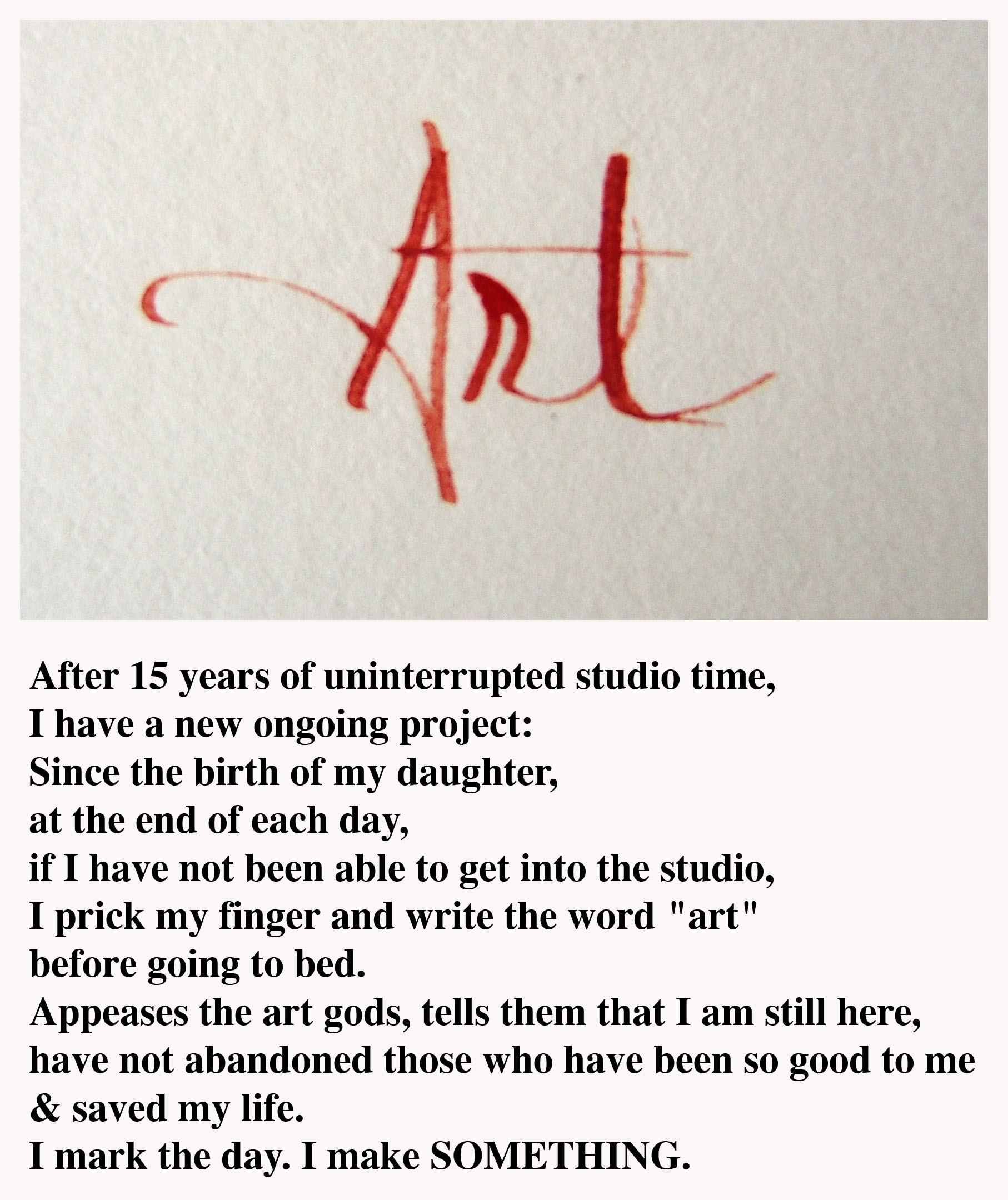

"Beauty," Dave Hickey once wrote, "is a weapon, you just have to aim it." In Kretz's hands, this weapon is trained upon the human landscape. A quote borrowed from Alain Arias-Mosson and left upon a page in one of Kretz's sketchbooks further emphasizes the artist's commitment to rendering subversively beautiful images of intense emotional and visual force: "The purpose of art is not a rarified, intellectual distillate - it is Life, intensified, brilliant life."